I recently survived a major parenting milestone: my child’s first high school party. With alcohol.

My 9th grader went to the party with a friend and a plan for how to not get pressured into drinking (carry a cup around without drinking from it so people don’t keep offering drinks). When she came home at 10:30 pm, alcohol-free, I was proud and relieved. Then I heard the details: the parents were home and apparently fine with a house full of 14-year-olds chugging vodka. Soda and chips were available and to my daughter’s relief, many kids besides her and her friend stuck with those sodas and chips. But others were clearly inebriated – throwing up in the toilet and unable to walk.

Here's the kicker: the parents told the kids that the police were on their way so everyone should leave. I don’t know the whole story but my impression is that for some reason these parents had no fears of legal repercussion. From what I’ve gathered, this lack of legal repercussions for parents is common in our local community – as is underage drinking. Hosted by adults.

As just one example of this permissive culture, one mom of high schoolers once told me, “Yeah my [high school] boys were out back drinking beers – I can’t stop them.”

I think she can. I think we can.

Why don’t we?

When I’ve shared this story with other parents, the common response has been: “parents these days can’t say No to their kids.”

I don’t know the family that hosted the party my young high schooler attended. I have no idea what went into their decision and if it was because they were uncomfortable turning down their child’s request. I just know they were present and aware that underage teens were drinking alcohol.

However, when we look at features of our modern parenting world over the last decade or more, the hypothesis that this may be a trend seems at least worth contemplating.1

Connection Over Consequences?

I have observed that a segment of parents – the ones most immersed in parenting guidance – worry that setting limits with their children may threaten the relationship. I’m sure we’ve all seen or lived some version of a young child writhing on the floor and screaming in a public place like a restaurant and the parent doing their utmost best to speak quietly and calmly to the child about how they are feeling.

This is just one (loud) sign of where we have gone astray with our near-obsessive focus on the relationship. You may have heard one of today’s most popular parenting experts say, “connection over consequences.” I have dissected the downsides of gentle parenting before, and the relationship fragility thesis is a big downside.

I agree with prioritizing the relationship in the big picture — investing time, energy, and attention to really know our child and figure out how you fit together as parent and child is critical. A healthy relationship serves as an important foundation for every aspect of parenting. So yes, in some ways I can see the validity of the “connection over consequences” mantra; however, it seems this has been translated by experts and parents alike into “connection instead of consequences all the time.”

It would help the very invested parents (like you who is reading a parenting Substack essay) to remember that our relationships with our children are sturdier than many social media parenting influencers lead us to believe. We don’t need to empathize with our child in every moment and explore the underlying reasons for the freakout (in fact, some kids will hate this and escalate further). We can be curious about the reasons for the public meltdown (Hungry? Exhausted? Sad?) and still scoop up that child and leave the restaurant.

I do not support a pendulum swing back to the old days of “because I said so” and “children should be seen and not heard.” But I do think the pendulum has swung too far into prioritizing and protecting the parent-child relationship as if it is a fragile Faberge egg that the wrong word or reaction will crack so that only shattered shell pieces remain.

Finding the Balance

The “connection over consequences” mantra has infiltrated our parenting psyches to the point that parents feel like this is a false binary choice: I either have a connection with my child or I give them consequences. It may not feel this black and white in our conscious thought process, but I fear it’s thrumming through our subconscious minds when we face difficult moments with our children.

In the first session of my Parent Smarter, Not Harder small group,2 one mother identified her goal as “balancing unconditional love, acceptance, support with expectations.” This tension between maintaining a positive relationship and enforcing expectations ran through all six of our sessions for all participants.

I also encountered this theme in a podcast interview when the host questioned whether expecting self-sufficiency ran the risk of our child not feeling nurtured. Recent parenting guidance has somehow led us to believe that these are mutually exclusive.

My training and expertise as a child clinical psychologist combined with fifteen years of being a mother has proven to me that instead of acting as opposing forces, “connection and consequences” (along with behavioral expectations, rules, and limits) work together for healthy child development—and healthy relationships.

At least one of my children has thanked me for our rule to not have phones in their rooms overnight. In her middle school years of navigating tricky social groups, this firm limit of charging her phone outside of her room during sleep gave her permission to opt out of what could be constant messaging.3 She welcomed the reprieve from social demands even if she wouldn’t have made the choice on her own.

Your child will likely not write you a thank-you note for your rules, limits, consequences, and expectations. My child’s spontaneous expression of gratitude about our phone rule came after much arguing about it in the preceding months. Whether or not a child ever acknowledges it out loud, rules/limits/consequences/expectations help children feel safe and communicate that you care about their well-being.

You CAN Take It Back

One place I see the false binary playing out is in the decision to give kids smartphones. Although there may be several factors influencing the decision, one I hear a lot is that once a child has a phone, parents can’t “take it back.” You absolutely can! And you can set limits around phone use, especially at younger ages when children need scaffolding to learn responsible use.

I don’t mean to suggest using “you’re going to lose your phone” as a threat for every transgression. Using a phone as a disciplinary weapon is not effective. But if the problem directly relates to using the phone – like sneaking the phone from its charging place overnight to be on social media or Snap until the wee hours instead of sleeping – that is grounds for scaling back phone freedom and tightening the reins.

This probably sounds like common sense and maybe many of you already parent along these lines. But I know so many parents who struggle to enforce and maintain limits that are unpopular with their kids. Why? Because it feels like a threat to the relationship.

But I can’t just blame the subtle psychic absorption of gentle parenting memes. We’re also exhausted.

So Tired

I have a weekly phone call with my best friend, a mother of two sons close to my kids’ ages. We often vent about struggles around our kids’ use of devices and their clever ways of circumventing limits. We have concluded that a main reason parents are seduced by the idea of a no-phone policy is that it is simply exhausting to regulate use once the phone is in their hands.

The problem is there can be real downsides to our children not having phones at a certain age, and adhering to the “no phone for you” rule may actually end up not only more exhausting, but also cause conflict and disconnection between you and your child. As I have previously argued, this relationship disruption could cause more damage than your child having a phone.

However, I understand the simplicity of how if there is no cell phone to fight about, life will be calmer. Obviously, this goes beyond phones. Especially for those of us with small (and big) people who love to argue, it can be soul-sucking to stick to our guns. I have given into many an argument simply because those master negotiators wore me down.

This is why we need to have clarity around when and where to expend energy on setting limits with our children. How can we activate our limit-setting with a resoluteness that even the most persuasive child can’t cause to waver? By doing a risk analysis.

Risk Analysis

How many times did your toddler attempt to wrestle out of that car seat – and how many times did you say “oh well we’ll just drive without you strapped in”? The risk calculation is crystal clear with car seats – those fragile, small bodies would not survive a serious car accident; it’s a no-brainer to push those thrusting hips into the car seat corners and muscle those pesky buckles until that satisfying click for safety.

Most areas of risk calculation aren’t as clear-cut – especially when we parent in a media world that flourishes from fear and hyperbole. For example, I realize my take on setting limits with phones and alcohol may seem like opposite advice: consider yes to giving your kid a phone but always no to permitting alcohol.

This is because every limit and chance to “just say no” is not created equally. I may throw up my hands and say “fine” to delaying my child’s shower one more day, but I will stand firm that we don’t give our children permission to drink alcohol as minors.4 The phone decision lies in murkier territory, depending on the child’s level of vulnerability and readiness. But again, it’s okay to say “yes,” and then “no,” if the situation warrants a change.

It’s hard to strike the balance of exploring a troubling trend while not coming across as blaming parents. I unequivocally don’t blame parents; I deeply sympathize. It is clear we are a generation of parents objectively overwhelmed by stress and struggling.5 We have also been inundated with messages about the fragility of our relationships with our children from well-meaning and pervasive sources. The bottom line is that many forces have converged to a point where everything feels so hard. No wonder that includes telling our children “No.”

Have you noticed parents having a hard time saying No to their kids “these days?” What are your thoughts?

In the Media

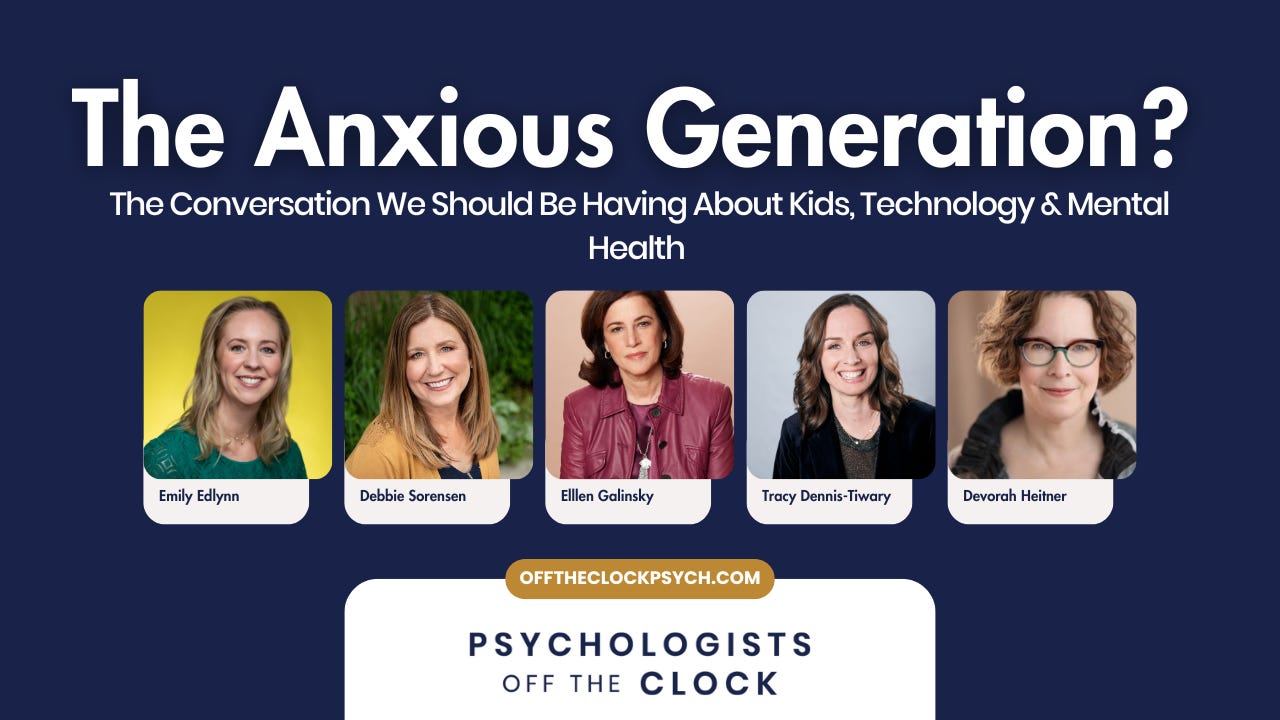

As Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation continues to make waves in parent and school communities, our Psychologists Off the Clock experts roundtable episode came out this week in our regular feed and on YouTube to offer an alternative to fear-based messaging around youth and technology. Please listen and share this episode to help shift the tides of fear-mongering into a more positive, productive direction for us and our children!

Speaking of fear-based parenting, did you see the recent headline about a mother in Georgia arrested for allowing her 10-year-old to walk alone in their community? Parents covered the story and included my thoughts along with free-range parenting pioneer, Lenore Skenazy. Even the AAP states that ten-year-olds are equipped to walk alone! The laws need to catch up and I as I say in the piece, parents should be encouraged to promote this independence, not penalized.

In this season of gratitude, I am truly grateful to each of you who has read, subscribed, liked, commented, and reached out personally. Being in community with all of you is a clear highlight of my year.

Gratefully,

Emily

Ha! You thought this was going to be about helping our kids not drink by “just saying no.” Did I get you? I love a good double-meaning.

We don’t have many rules about smartphones, but removing phones from bedrooms overnight to preserve sleep is non-negotiable.

When framing setting limits in the context of risk analysis, some have argued that the smartphone is an equivalent danger to alcohol. This is called a false equivalence: smartphones involve a nuanced combination of risk and benefit that differs across the individual child. There is no benefit, only risk, of alcohol infiltrating the adolescent brain and body. If you are interested in more information, follow Jessica Lahey on Instagram and check out her book, The Addiction Inoculation: Raising Healthy Kids in a Culture of Dependence.

As documented in the U.S. Surgeon Generals’s recent public health advisory, Parents Under Pressure.

One of our main jobs as parents is to teach kids how to be in relationships. Something I think is missing from the extreme forms of "gentle parenting" is a recognition that other people have needs and feelings, too. Yes, your feelings matter, but so do others', and sometimes your feelings are not the most important. I had a client once, a young girl who hated, hated, hated having her picture taken and didn't hesitate to let everyone know it at the top of her lungs. When grandma's big birthday was coming up, and family members were going to be gathering from near and far, I said to the girl, "You really hate getting your picture taken. It makes you feel uncomfortable and self-conscious, and it's boring to stop what you're doing and look at the camera or line up with everyone. I hear you. Whose feelings are most important at Grandma's birthday party?" Recognizing the answer to this question helped her endure the family photos at the big event. Our kids feelings matter, but they're not always the most imporant thing.

Yeah, 14 year olds drinking to the point of vomiting sounds super alarming. And the *idea* that it was happening with the support of some parents is also alarming. Though, as you said, you don't know the whole story, and I am curious about what the story really is. What needs were they trying to meet? We have no idea.

I also found the phrase "connection over consequences" super interesting as I have never heard of it. But, to be fair, I spend almost no time on social media besides facebook. I *have* heard of "connection before correction", which makes sense. It seems that in your analysis of the "consequences" you are actually meaning punishments. Is that right?

I read this with curiosity, because of the conflation, in your title, of gentle parenting and permissive parenting. Gentle parenting has a big umbrella, but "no" is definitely a word that gets used. Your rule of no phones in rooms overnight makes total sense, in terms of meeting needs for proper rest, safety, predictable expectations etc. And it could absolutely fall under the umbrella of gentle parenting, though I got the impression you think it doesn't. Did I understand that correctly?

I am in full agreement with you about scooping up a melting child and leaving a restaurant, and with the idea that it can happen while still being curious and empathic about what the child is needing. But I think this also falls under gentle parenting. More specifically, respectful parenting.

I think we're largely on the same page. But I have some concern about the "permissive" and "gentle" being read as the same thing, which, in my world, they aren't at all. And just writing that sentence, to me, invites judgment of permissiveness. I would rather be curious as to what longings a parent has that leads them towards permissiveness.

How is it for you to get this response?